The history of Canada’s residential schools was recently documented through a unique lens when international photojournalist Daniella Zalcman visited the province last month.

Based out of New York and London, Zalcman was in Saskatchewan from July 31 to Aug. 13 working on her most recent project.

After presenting a series on the rise of homophobia and anti-sexuality laws in Uganda, the Pulitzer Centre on Crisis Reporting, who Zalcman works with, asked her to look into another story that revolved around lives affected by HIV.

With some research, Zalcman found that Canada’s HIV numbers, particularly within indigenous communities, are high above other colonialized countries. With further research Zalcman found those numbers correlated with residential school survivors.

Zalcman spent most of her time in Regina, visiting communities around the city where she spoke and photographed residential school survivors. In total, Zalcman conducted interviews and took portraits of 45 survivors or children of survivors.

“The people were just incredible,” Zalcman said. “It’s kind of an uncomfortable thing to walk up to a complete stranger, infer they are indigenous and then try within the first 10 minutes of the conversation to figure out whether or not they went to a residential school.”

Most of the survivors were willing to share their stories with her, however, at times Zalcman said she wasn’t prepared for what she was about to hear.

“I work on a lot of heavy stories but this was by far the darkest set of interviews I’ve ever gone through,” Zalcman said. “I think maybe one of the most shocking things is how similar a lot of the stories are … these awful unspeakable things that just happened to every single person as a kid.

“It’s really shocking and I’m kind of bewildered and saddened that more (people) don’t know about it.”

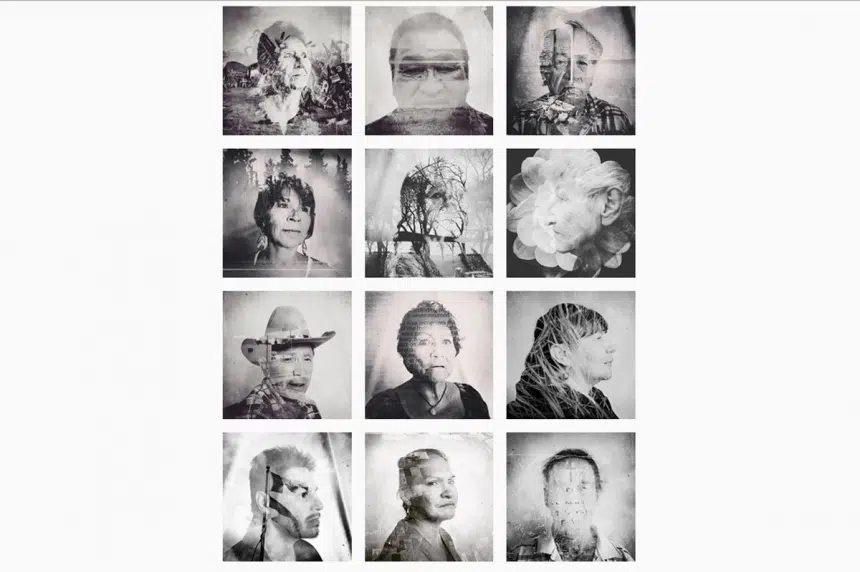

Last week, Zalcman was invited to ‘take over’ The New Yorker photo department’s Instagram account where she posted the portraits and write-ups of several survivors. Using multiple exposures, the black and white portraits are overlaid with symbols and items representing each victim’s story. The effects on the photos served a key purpose in the message behind them, Zalcman said.

“In this day and age we are so over saturated with media and we’re so over saturated with terrible stories … there’s only so much of that you can look at without just sort of going numb and not registering the pain and the suffering that you’re seeing.

“We do get desensitized to that and so in a way, I was almost trying to soften these images to make them not only different … but to sort of soften the tone before they can read the text and realize what exactly is happening. I think that’s necessary sometimes.”

The effect also served the purpose of hiding some of the people’s identity. While Zalcman said they were comfortable sharing their stories, a couple had reservations with showing their faces.

“They asked me if I could obscure their identity, and this allowed me to do this effectively while still including them in their image.”

Zalcman is currently working on several projects including a multi-story piece on off-the-grid living, and continuing her work with anti-sexuality and homophobia in Uganda. She would also like to come back to Saskatchewan someday to follow up on her most recent project.

“In the two weeks I spent in Saskatchewan, I shot 45 portraits and conducted 45 interviews. I would love to have 80 – one for every 1,000 living survivors,” Zalcman said.

“I would like to turn this into an exhibit just because I think it is a more accessible and better way to get content out to the general public and I’m going to make sure I do my best to make sure that happens.”

You can see project on The New Yorker photo department’s Instagram and more photos from Zalcman here.

Follow on Twitter: @khangvnguyen