They’ve been here for millions of years but have only just been found.

Scientists at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum showed off all the fossils and specimens it discovered across the province over the summer.

They include:

- The skull of a baby Edmontosaurus (duck-billed dinosaur) found near Shaunavon.

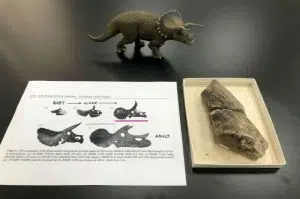

- A horn core of a baby Triceratops found in Grasslands National Park.

- The skull of a baby Elasmosaur (long-necked marine dinosaur) from Lake Diefenbaker.

- Partial skeleton of a juvenile Bronotothere (38 million year-old rhino-like mammal) discovered near Eastend.

- Teeth from a Gorgosaurus (a big carnivore that looks like Albertosaurus), and Ankylosaurs (armoured dinosaurs with clubbed tails) from near Consul.

- Pieces of amber collected near Bengough were found to contain insect inclusions from the Cretaceous period, including a newly discovered species of wasp.

Dr. Emily Bamforth showed off her biggest find of the summer — part of the skull (upper jaw) of the Edmontosaurus. It’s considered the largest duck-billed dinosaur that ever lived and was as big as a T-Rex. They lived around the same time, right before extinction, about 145 million years ago in the Cretaceous period.

This skull is only the second of its kind ever found in Saskatchewan. The first was found in 1924.

When it was discovered near Shaunavon, it was encased in mud. They knew it could be something exciting but didn’t realize what they found until they brought it back to the lab. They chipped off the mud and saw teeth.

“That was one of those moments I wanted to do cartwheels because skulls of dinosaurs in Saskatchewan, especially of this type of dinosaur, are vanishingly rare,” said Bamforth.

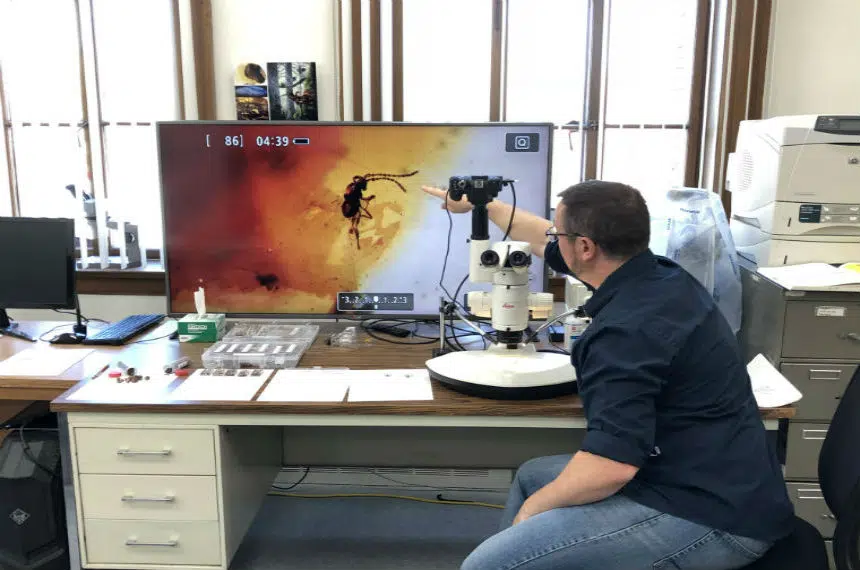

Preserved in amber

Ancient insects trapped in fossilized tree resin and preserved over millions of years provide a glimpse into various stages of evolution.

Ryan McKellar is the museum’s curator of invertebrate paleontology and Saskatchewan’s lead amber researcher.

His team turned up the first 15 insect inclusions from Saskatchewan amber while working in the Big Muddy badlands near

Bengough.

In this case, they found aphids, midges and a well-preserved new species of wasp. Some of them are microscopic, just one millimetre long.

These specimens help fill in the evolutionary gap as scientists learn where today’s insects come from.

“We don’t have good coverage from the end of the Cretaceous until after the extinction event. Saskatchewan is one of the few places on Earth where you can look at insects in that time window,” said McKellar.

McKellar explained that’s partially because of the layers of sediment that were laid down millions of years ago, partially from the exposure created by glaciers, river systems and Saskatchewan’s dry climate.