From nearly the moment they roared down the runway and took off in their new Boeing jetliner, the pilots of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 encountered problems with the plane.

Almost immediately, a device called a stick shaker began vibrating the captain’s control column, warning him that the plane might be about to stall and fall from the sky.

For six minutes, the pilots were bombarded by alarms as they fought to fly the plane, at times pulling back in unison on their control columns in a desperate attempt to keep the huge jet aloft.

For six minutes, the pilots were bombarded by alarms as they fought to fly the plane, at times pulling back in unison on their control columns in a desperate attempt to keep the huge jet aloft.

Ethiopian authorities issued a preliminary report Thursday on the March 10 crash that killed 157 people. They found that a malfunctioning sensor sent faulty data to the Boeing 737 Max 8’s anti-stall system and triggered a chain of events that ended in a crash so violent it reduced the plane to shards and pieces. The pilots’ struggle, and the tragic ending, mirrored an Oct. 29 crash of a Lion Air Max 8 off the coast of Indonesia, which killed 189 people.

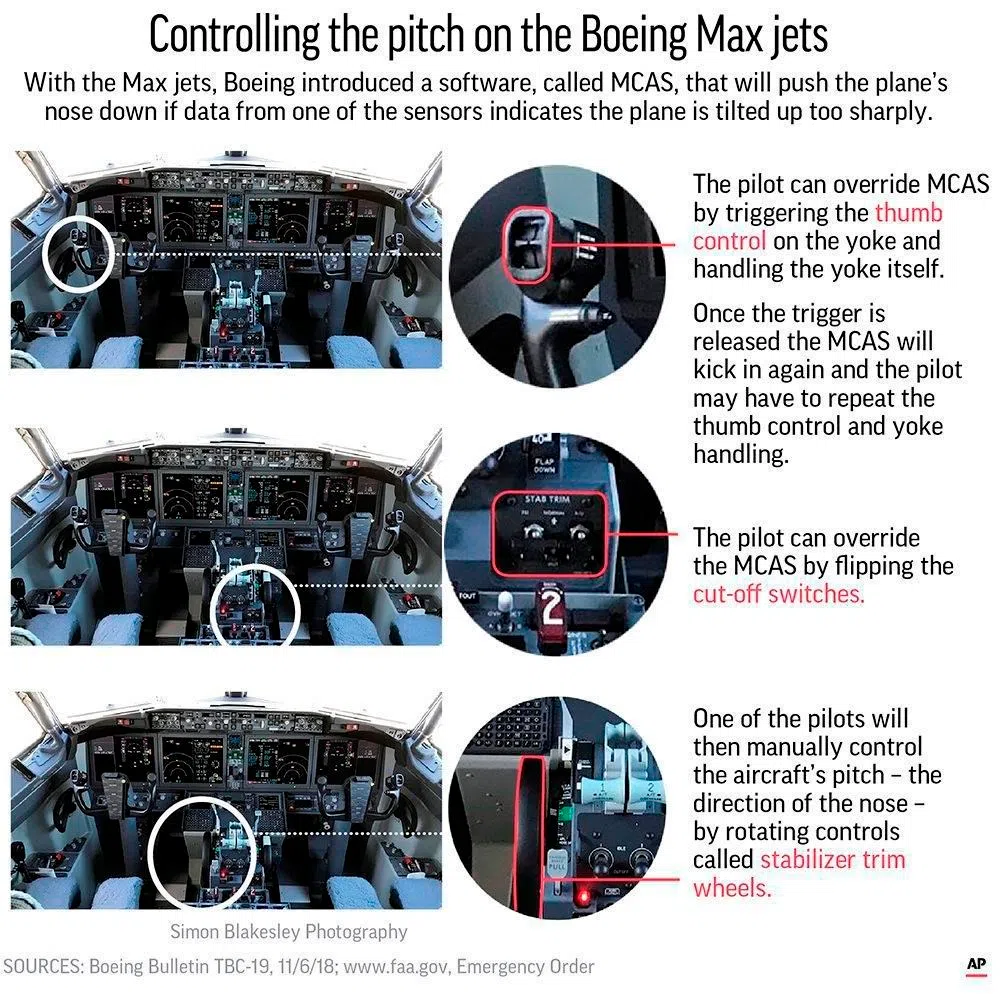

The anti-stall system, called MCAS, automatically lowers the plane’s nose under some circumstances to prevent an aerodynamic stall. Boeing acknowledged that a sensor in the Ethiopian Airlines jet malfunctioned, triggering MCAS when it was not needed. The company repeated that it is working on a software upgrade to fix the problem in its bestselling plane.

“It’s our responsibility to eliminate this risk,” CEO Dennis Muilenburg said in a video. “We own it, and we know how to do it.”

Jim Hall, a former chairman of the National Transportation Safety Board, said the preliminary findings add urgency to re-examine the way that the Federal Aviation Administration uses employees of aircraft manufacturers to conduct safety-related tasks, including tests and inspections — a decades-old policy that raises questions about the agency’s independence and is now under review by the U.S. Justice Department, the Transportation Department’s inspector general and congressional committees.

“It is clear now that the process itself failed to produce a safe aircraft,” Hall said. “The focus now is to see if there were steps that were skipped or tests that were not properly done.”

The 33-page preliminary report, which is subject to change in the coming months, is based on information from the plane’s flight data and cockpit voice recorders, the so-called black boxes. It includes a minute-by-minute narrative of a gripping and confusing scene in the cockpit.

Just one minute into Flight 302 from Addis Ababa to Nairobi in neighbouring Kenya, the captain, Yared Getachew, reported that they were having flight-control problems.

Then the anti-stall system kicked in and pushed the nose of the plane down for nine seconds. Instead of climbing, the plane descended slightly. Audible warnings — “Don’t Sink” — sounded in the cockpit. The pilots fought to turn the nose of the plane up, and briefly they were able to resume climbing.

But the automatic anti-stall system pushed the nose down again, triggering more squawks of “Don’t Sink” from the plane’s ground-proximity warning system.

Following a procedure that Boeing reiterated after the Lion Air crash, the Ethiopian pilots flipped two switches and disconnected the anti-stall system, then tried to regain control. They asked to return to the Addis Ababa airport, but were continuing to struggle getting the plane to gain altitude.

Then they broke with Boeing procedure and returned power to controls including the anti-stall system, perhaps hoping to use power to adjust a tail surface that controls the pitch up or down of a plane, or maybe out of sheer desperation.

One final time, the automated system kicked in, pushing the plane into a nose dive, according to the report.

A half-minute later, the cockpit voice recording ended, the plane crashed, and all 157 people on board were killed. The plane’s impact left a crater 10 metres deep.

The Max is Boeing’s newest version of its workhorse single-aisle jetliner, the 737, which dates to the 1960s. Fewer than 400 Max jets have been sent to airlines around the world, but Boeing has taken orders for 4,600 more.

Boeing delivered this particular plane, tail number ET-AVJ, to Ethiopian Airlines in November. By the day of Flight 302, it had made nearly 400 flights and been in the air for 1,330 hours — still very new by airline standards.

The pilots were young, too, and between them they had a scant 159 hours of flying time on the Max.

The captain, Getachew, was just 29 but had accumulated more than 8,000 hours of flying since completing work at the airline’s training academy in 2010. He had flown more than 1,400 hours on Boeing 737s but just 103 hours on the Max. That may not be surprising, given that Ethiopian Airlines had just five of the planes, including ET-AVJ.

The co-pilot, Ahmed Nur Mohammod Nur, was only 25 and was granted a license to fly the 737 and the Max on Dec. 12 of last year. He had logged just 361 flight hours — not enough to be hired as a pilot at a U.S. airline. Of those hours, 207 were on 737s, including 56 hours on Max jets.

Thursday’s preliminary report found that both pilots performed all the procedures recommended by Boeing on the March 10 flight but still could not control the jet.

While Boeing continues to work on its software update, Max jets remain grounded worldwide. The CEO said the company is taking “a comprehensive, disciplined approach” to fixing the flight-control software.

But some critics, including Hall, the former NTSB chairman, question why the work has taken so long.

“Don’t you think if Boeing knew what the fix was, we would have the fix by now?” he said. “They said after the Lion Air accident there was going to be a fix, yet there was a second accident with no fix. Now, in response to the worldwide reaction, the plane is grounded and there is still not a fix.”

David Koenig, The Associated Press