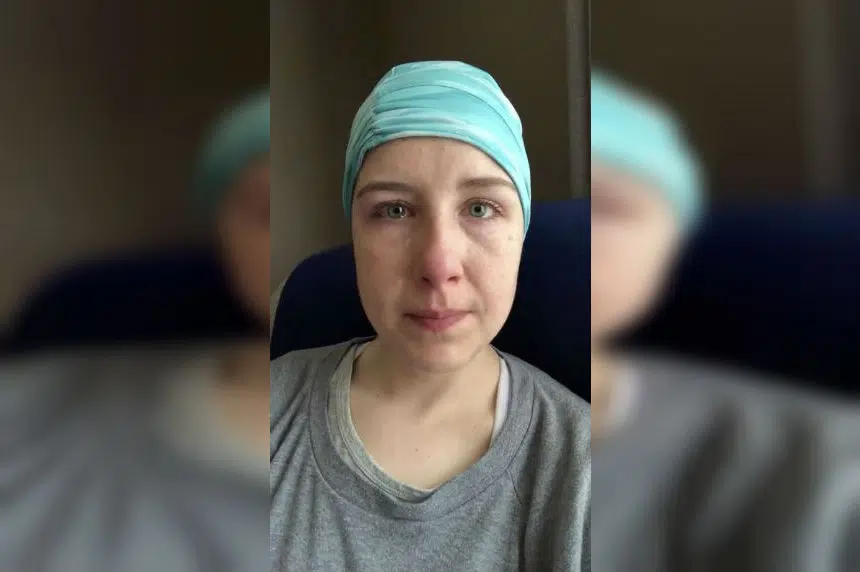

HALIFAX — A viral video made by a frustrated young Nova Scotia mother who says she waited two years for her cancer diagnosis can’t be ignored, says the president of the Canadian Medical Association.

Dr. Gigi Osler called the situation described by 33-year-old Inez Rudderham “heartbreaking.”

“We have to pay attention to it because I think it is a sign of the challenges our health care system is facing right now,” Osler said in an interview Friday.

In an emotional Facebook video that has been viewed more than 2.6 million times, Rudderham says she went undiagnosed with Stage 3 anal cancer for two years due to her lack of access to a family doctor.

She says she had to seek care in emergency departments, and was only diagnosed after three trips to the ER. She also says she won’t be able to get the mental health services she needs to deal with the stress brought on by her ordeal until July.

Rudderham described her case as the “face of the health-care crisis in Nova Scotia,” and has asked to meet with Premier Stephen McNeil.

Osler said lack of access to primary health care is not unique to Nova Scotia — New Brunswick and British Columbia, for example, have similar issues.

She said Canada’s health care problems are “complex and interwoven” and won’t be solved by simply throwing money at the system.

Nova Scotia’s ratio of 257 doctors per 100,000 people is the highest in the country. And yet there were 51,119 people on a waiting list for a family physician in the province as of March 1.

Osler said it may be time for Ottawa to take the lead in dealing with the human resources problems, adding that there needs to be a “top to bottom” examination of the health care system from coast to coast.

“We need some bold solutions and some bold leadership,” said Osler, whose group represents Canada’s doctors.

And while the CMA doesn’t have a position on whether the Canada Health Act should be changed, Osler said it’s time for Canadians to have an “open and frank discussion” about issues in and around the legislation.

As an example, she pointed to Rudderham’s “excessive” wait for mental health services.

“Other than psychiatric care, mental health coverage isn’t in the Canada Health Act, but should it be? Is it time to include mental health services … is it time to consider home care in the act?”

John Malcom, a former chief executive of the Cape Breton Health Authority, said he believes there are direct links between the shortages of primary care physicians and missed diagnoses such as occurred in Rudderham’s case.

“The family doctor knows you when you’re healthy and when you’re not,” he said in an interview.

“When you go into a hospital, whether it’s an emergency room or a walk-in room or under a specialist’s care they see you as a sick person. They don’t know what you’re like when you’re healthy.”

That knowledge of a person’s medical history and their wider lives often provides “the spark” that helps a physician suspect a series illness in a young person, said the veteran health administrator.

The solution to shortages of family doctors is part of a wider national problem that is going to require years to turn around, Malcom said.

He argues it threatens the health of patients across Canada.

Malcom said provincial governments must increase the number of medical students and ensure all of the two-year specialist training spots – known as residencies – be filled across the country.

According to 2017 figures from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), Nova Scotia has 1,234 family doctors and 1,222 specialists for an overall physician total of 2,456, serving a population of about 965,382.

Geoff Ballinger, manager of physician information at CIHI, said there’s no way of telling at this point what the preferred ratios should be because health care is delivered differently in each province.

“There is no benchmark ratio,” said Ballinger. “Even if there was, that benchmark ratio would probably change over time as well as populations change in terms of aging and so on.”

Nova Scotia Health Minister Randy Delorey said Friday the provincial government has recognized the public’s concerns and is taking measures around doctor recruitment and retention, including an international recruitment stream.

He also pointed to an increase in residency seats of 10 for family physicians and 15 for specialists who are training in the province.

“That’s in response to the recognition that where a physician trains and completes their residency training, they are more likely to stay to set up practice,” said Delorey.

He said he believes the province’s efforts are “starting to pay off.”

“Are we all the way there? No. Are we going to continue our efforts? Yes.”

In her video, Rudderham says she has received 30 rounds of radiation to her pelvis, which has left her “barren and infertile.”

Rudderham says she was brushed off when she took her health concerns to emergency rooms.

“It’s OK though, right? Because they caught it. They caught it when it was Stage 3,” says a teary Rudderham.

“To the premier of Nova Scotia, I dare you to take a meeting with me … and tell me there is no health-care crisis.”

Dr. Gary Ernest, president-elect of Doctors Nova Scotia, says the video demonstrates the province’s family doctor shortage constitutes “a health crisis.”

John Gillis, spokesman for the Nova Scotia Health Authority, said Friday officials had seen the video and “been affected” by it, and are reaching out to Rudderham to address her concerns.

“Her story reminds each of us why we work in health care — day by day we want to help Nova Scotians be well, and care for them when they are ill,” he said in a statement.

— With files from Michael Tutton

Keith Doucette, The Canadian Press