OTTAWA — The federal government says it can’t measure how many people actually receive emergency-alert messages on their phones.

The Alert Ready system is designed to notify Canadians of potentially dangerous situations — everything from terrorism and explosions to flash floods and tornadoes. It is also the system used to broadcast Amber Alerts when a child goes missing.

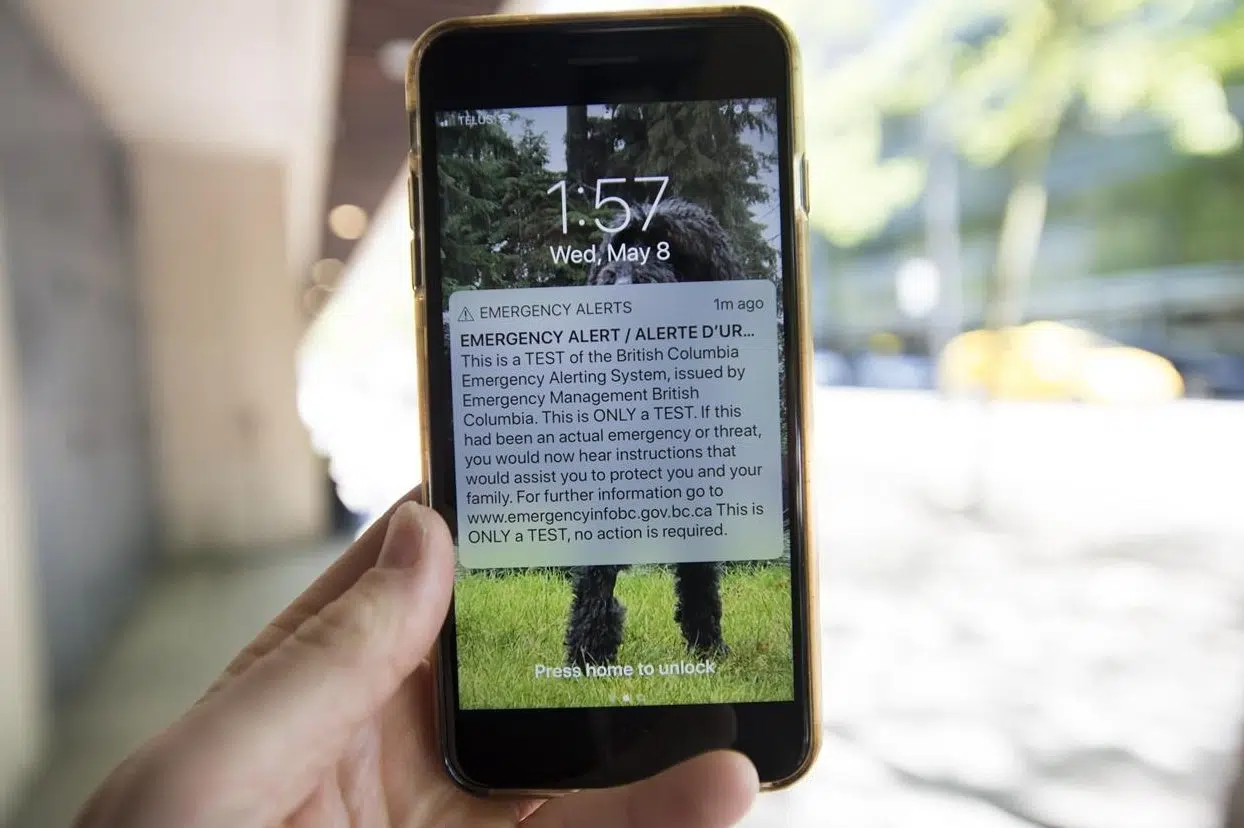

Public Safety Canada spokesman Tim Warmington said the most recent test of the system, conducted May 8, produced good results.

“In all participating (provinces and territories), alerts were successfully processed and distributed, and wireless carriers confirmed having distributed the alert over their networks without issue,” Warmington said.

However, he acknowledged, there is no way to know how many people actually got the warnings.

“Alert distributors do not have a mechanism to measure how many Canadians viewed or received the alert, but the confirmation in each jurisdiction indicates it was successfully distributed.”

The system has been under scrutiny this week following a tornado in Ottawa’s east end that arrived without warning around 6 p.m. Sunday night.

Environment Canada is working with other partners to figure out what happened, although part of the problem is that the storm developed so quickly, it struck before most of the alerts were sent.

Another problem is that Ottawa — where the tornado actually hit — was never included in the area where the warnings were issued.

The Alert Ready system can be targeted to very small areas, with the message sent to phones connected to even just a few cell towers. On Sunday the messages were sent to towers covering Gatineau, Que., other parts of western Quebec and a county south

Radio and television stations have been required to broadcast the alerts since 2015, but wireless providers were only added in April 2018.

Public Safety Canada says people should receive the alerts if their phones are powered on and connected to an LTE network. In silent mode, the alert will come in and be displayed on the screen but the phone will not make a sound.

Erik de Groot, a meteorologist at Environment and Climate Change Canada, said Sunday’s tornado was not typical but officials are still reviewing everything that happened.

“We are looking back to see what we can do to improve,” he said.

De Groot said the main constraint was the sudden onset of the storm. Most weather conditions that could lead to tornadoes can be predicted several days in advance using radar and other forecasting tools, with advance warnings sent out in plenty of time.

The one that touched down in Ottawa on Sunday evening wasn’t foreseen at all, said de Groot.

Conditions were not conducive to the formation of a tornado and it was only when someone spotted a funnel cloud near the airport in Gatineau, Que., that alerts were issued. The decision was then made to expand the alert to Gatineau, other parts of western Quebec and a region south and east of Ottawa.

“Hindsight is always 20-20,” he said. “In those first stages it’s difficult to predict and the forecasters did the best they could.”

Alert Ready only sends out the warnings to the areas the system is told to and for extreme weather, those decisions are made by Environment Canada.

The tornado in Ottawa caused damage to buildings, but only one minor injury was reported.

Some residents in the western Ottawa town of Dunrobin, where an EF3 tornado touched down last September, have credited the Alert Ready system for getting them to take cover before the storm flattened their homes.

Mia Rabson, The Canadian Press