OTTAWA — The federal government is promising to piggyback on existing projects and networks as much as possible to expand broadband access to rural communities as part of two reports being made public today.

Officials are also looking to rework some programs to make it easier for rural communities to benefit from federal spending as part of the related strategies.

But aside from specific targets to connect Canadians to high-speed internet service, the rural strategy is largely without benchmarks.

Rural Economic Development Minister Bernadette Jordan says the aspirational tone of the document reflects concerns from rural communities about a one-size-fits-all approach.

The government isn’t announcing any new spending, but ways to more efficiently dole out promised cash, including $6 billion worth of plans to connect every household in the country to high-speed internet by 2030.

Jordan says the plans are not designed to help the Liberals in this fall’s federal election, but rather reflect the concerns rural Canadians raised during consultations.

“We want to make sure going forward that we are addressing those concerns,” Jordan said in an interview.

“In reality, rural communities haven’t said, ‘We want you to come in and fix our problems.’ What they’ve said is, ‘We want to work in partnership with you,’ and that, going forward, is the biggest takeaway for us — is how do we make sure that we are working in partnership with rural Canada, how do we make sure that everything we’re doing is looked at through a rural lens?”

Jordan said what was needed was a way to pull together all the different spending programs that provide money to rural communities. Sometimes small municipalities can’t get past hurdles such as complex application packages for federal funding.

Rural Canada comprises an estimated 30 per cent of the national economy but accounts for a smaller percentage of the national population.

The 2016 census showed that 82 per cent of the Canadian population lived in large and medium-sized cities, one of the highest urban concentrations among G7 nations, but percentages vary by province. For example, almost half of those in Atlantic Canada live in rural communities, compared to fewer than 10 per cent in British Columbia.

Rural communities tend to have higher percentages of Indigenous residents, fewer newcomers to the country and older populations than urban centres do.

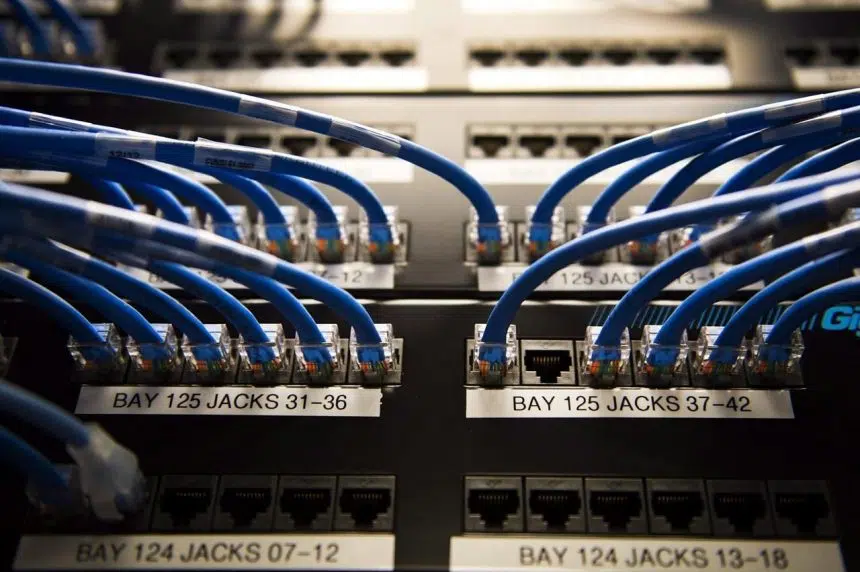

While housing affordability is a major concern in rural communities, the top one is connectivity. About 37 per cent of rural households had access to internet connections with download speeds of 50 megabytes per second, compared to 97 per cent of urban homes.

Officials hope to reduce the costs of upgrading connections by finding ways to identify infrastructure projects where fibre-optic cable can be laid at little cost, such as when a rural community reconstructs a road.

A major cost of building and operating broadband networks comes from poles, underground ducts and towers, and piggybacking on planned construction work could halve federal costs, officials say.

Places like municipal offices, libraries, schools, and hospitals will be given priority for any projects, the rural broadband strategy says, because there are more people using connections at once. When such a community institution is being connected, that can also help make the case to extend broadband to surrounding homes, the government says.

The strategy also says that federal officials are looking at ways to provide a secondary market for wireless spectrum, to grant licences in small areas and provide better cellular service.

Jordan Press, The Canadian Press