Orange Shirt Day at Regina’s downtown public library was anything but monochromatic, or quiet.

Indigenous singers and dancers filled the library on Monday with the sounds of drumming and jingle dancing. In addition to celebrations and dignitaries speaking, students from Balcarres Community School set up their artwork.

It’s intended to honour residential school survivors and victims, and to begin a process of reconciliation so that non-Indigenous people can learn of the schools’ legacy and Canada’s role as an enabler of the schools’ abuses.

Brad Bellegarde is a hip hop artist who also works as an Indigenous relations adviser with the City of Regina.

His family is from the Carry the Kettle Nakoda Nation and the Little Black Bear First Nation, but he grew up in Regina, attending Miller High School.

That’s where he first had the chance to work with non-Indigenous people to tell them about residential schools; both of his parents attended the Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School.

He said he was part of a group of students that were in a pilot project Native Studies class at Miller.

“There were maybe three or four students that were of European background. Just every-day getting to educate them on something was so eye-opening,” he said. “Every day, I’d just be able to share something about powwow, about being First Nations, about what a reserve is.”

He said events similar to the one put on by the Balcarres students are examples of how education is changing to include everyone in gaining an understanding of the history of residential schools.

“Those types of conversations are happening now regularly when I go into classrooms,” Bellegarde said. “And I think it’s really cool to see the inspiration kids get about being proud of who they are and their ancestry.”

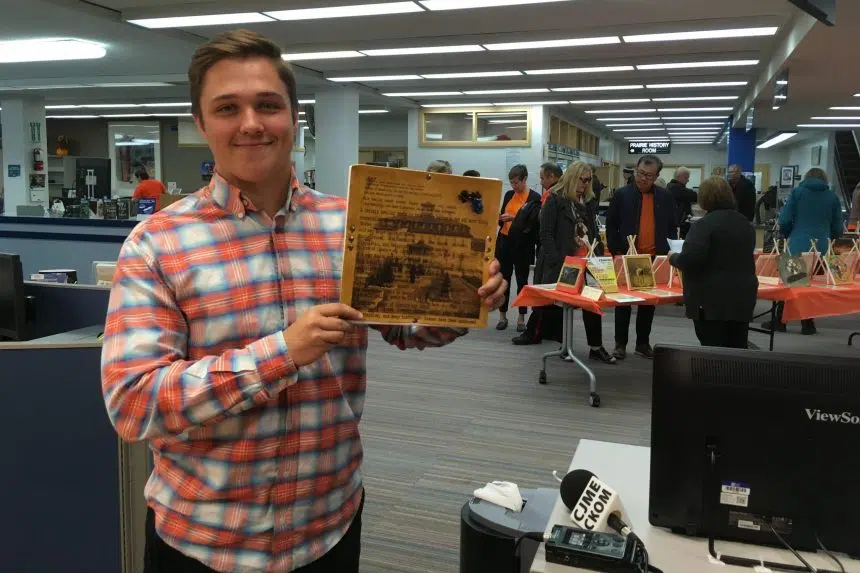

Grade 12 student Jacob Stoll was assigned to create a piece based on the 59th call to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

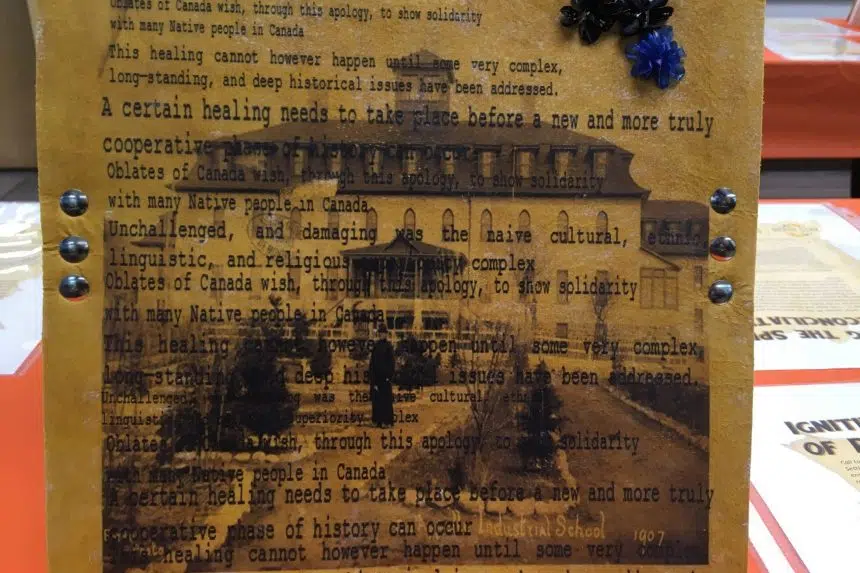

That call to action states: “We call upon church parties to the Settlement Agreement to develop ongoing education strategies to ensure that their respective congregations learn about their church’s role in colonization, the history and legacy of residential schools, and why apologies to former residential school students, their families, and communities were necessary.”

He used Photoshop, animal hide, the call to action and an image of the Qu’Appelle residential school to create the canvas work.

“This just has to heal over time and really has to come together,” he said of the churches’ legacies. “The churches have to do everything they can to make right about what happened and how the past was. We are taking steps to reconciliation and we’ve put in the work, and that’s something everyone needs to do.”

Stoll said he’s glad to have grown up in Balcarres, which is near four First Nations and has a strong mix of Indigenous and non-Indigenous students.

“Lots of my friends are Indigenous, and I’ve grown up going to powwows (with friends),” he said. “It’s really huge and I feel a connection there as well.”

That made the chance to work on a piece of art that examines Indigenous history all the more special, he said.

Bellegarde agreed that education and making connections is a key step to building relationships between different ethnicities and continuing reconciliation.

“We can all actually point those children in the right direction, and hopefully we can all change the direction of those young people’s minds,” he said.