As a kid, Tim Haltigin quickly became familiar with stars in the night sky.

They illuminated the farm near Canora where he grew up. His curiosity was as constant as the constellations that kept him company.

“I would look up and just wonder what was out there and how can we explore it,” said Haltigin. “To think that here we are potentially picking one of those dots and bringing a piece of it back to Earth is really incredible.”

Those early days in rural Saskatchewan planted a celestial seed that eventually grew into a career for Haltigin at the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), which landed him an important role in NASA’s Perseverance Mars Rover mission.

Feb. 18 wasn’t just any other day for Haltigin. It was an exercise in multi-tasking. He was at home, feet up, watching the landing on TV beside his wife and daughters on the couch, while wearing a headset talking to his colleagues from NASA.

Then, touchdown.

“There was celebration on the screen, there was celebration in my headset, there was celebration on the couch,” he said. “It was an incredible moment.”

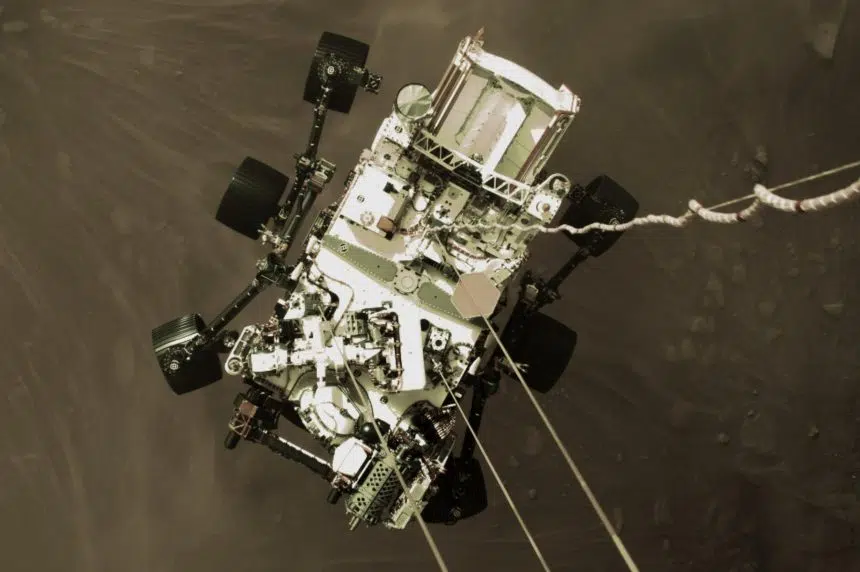

Perseverance — or Percy as the rover has been nicknamed — has been living on the red planet ever since. Haltigin said the rover is currently getting a sense of its surroundings, while sharing images of those surroundings with Earth. His team is ensuring the vehicle is safe and all equipment is functioning properly.

Percy didn’t come alone. It’s equipped with a helicopter to be deployed for several months’ worth of test flights sometime in the near future.

The journey to the red planet

Haltigin’s path to the CSA was anything but straight.

After starting his undergraduate in biochemistry, he realized research on malaria didn’t maintain his interest. He switched to geography for his master’s and studied how to rehabilitate trout habitats in rivers, and understand the relations between river flow and sediment transport. It was around this time friends of his suggested he enter a competition with them.

It would change his path entirely.

The competition was sponsored by the European Space Agency. Its subject matter was how to find water on Mars.

“I was sitting with them and I was like, ‘Listen, I don’t know anything about this but I make really good PowerPoint presentations and I really like space, so let me help,’ ” Haltigin laughed.

That help got them through round after round all the way to the competition’s finals in Barcelona, Spain. Ultimately, they didn’t win. Haltigin’s involvement did lead the professor who had been helping the team to ask if Haltigin wanted to do a PhD related to finding water on Mars.

Up to the Canadian high arctic Haltigin went to compare icy terrains there similar to those on Mars. It got the CSA’s attention. More than a decade later, he’s now the senior mission scientist in planetary exploration at the agency.

Searching for life

Landing on Mars is just the first phase for Perseverance.

Haltigin is helping lead the international campaign to bring samples back to Earth within the next decade. He’ll have to help decide who’s going to work on the samples, how they’ll be distributed and how scientists around the world, including in Canada, will have access.

“It’s profound,” he said. “We’re addressing one of the most fundamental questions of humanity with this mission which is: Are we alone in the universe?”

The location the rover landed in is Jezero Crater. Haltigin said researchers have overwhelming evidence that three billion to four billion years ago, there was a giant body of standing water — a lake into which a river flowed. That river brought and left behind sediments that eventually hardened into rock.

“Rocks are incredible storytellers. So even though the present-day climate and environment on Mars is very, very different than it used to be, these rocks will tell us what it was like, what the atmosphere was like, potentially what the water was like. What’s really exciting for us is that if life had ever arisen, it could have been preserved in these rocks,” said Haltigin.

“If we do detect signs of life, I can only imagine the types of questions and scientific investigation that it would trigger because I think one of the first things you need to do is to figure out is that life the same as on Earth and if so why? But if it’s different, then what we would have is evidence that life arose somewhere else.”

With the current surface of Mars bathed in radiation, void of liquid water and with a thin atmosphere, Haltigin said the probability of finding anything currently alive is very low.

“It’s not that we would be looking for actually living organisms but rather the signs they left behind,” he said.

Following in cosmic footsteps

The future is exciting for Haltigin.

“Certainly we’ll be visiting Mars I would guess within the next 20 years,” he predicted.

The technology may not be established to get people there and back safely quite yet, but Haltigin said scientists are working on it.

His excitement stretches beyond that. It’s not only rooted in what kinds of samples that will be brought back from Mars, but also what the next generation will find in those rocks.

“It’s our job to bring them back but it’s very much students’ job now to get ready to work on them because it’s kids in high school and in grade school and kindergarten and people that haven’t even been born yet that are going to be making those discoveries over the next 30 to 50 years,” he said.

“I would say, ‘Just get ready because we’re bringing you some amazing, amazing material to work with.’ ”

It’s a goal that may seem to be as far-reaching as the stars Haltigin once looked up at in rural Saskatchewan, but becoming a space scientist doesn’t have to be.

“Science is mischaracterized as being very serious and only experts can do it and you can never be wrong and never make mistakes. All of that’s completely wrong. We make mistakes all the time and we have fun doing it. It’s all about the journey. It’s about asking that next question,” he explained.

Curiosity is a good thing, Haltigin said, and he urged kids, teens and anyone else with an interest or desire to succeed to never stop asking questions.

It’s that same curiosity that baited him outside his home near Canora, to study the same night sky he once looked up at as a boy.

“It’s the land of the living skies for a reason,” he said.