When you enter the gates of Wanuskewin Heritage Park, you experience a different feeling.

And that is likely tied to the thousands upon thousands of years of history — all tied to the Opimihaw valley.

“The land is really the centre of Wanuskewin. This is a very special place; you feel it when you walk in. Especially with the bison here — it feels special,” curator Olivia Kristoff said as she took 650 CKOM through the park’s latest exhibit by Ontario-based Indigenous artist Mary Ann Barkhouse.

Aptly named “Opimihaw,” the exhibit features multiple pieces that all tie into one specific theme — the ecology of the Opimihaw valley.

Barkhouse said the inspiration came from a walk she had a few years ago with archaeologist and founder of Wanuskewin, Dr. Ernie Walker.

“I was very inspired,” she said. “Just about everything you see in the exhibition; there’s something about that valley that has seeped into the materials and the pieces and the imagery, at this time of not only environmental renewal with the reintroduction of bison to the property but also with Indigenous culture and renewal.

“Although there (are) so many challenges facing us, especially right at this very moment, I hope that people can take away from the exhibition these ideas of all the important characters that are part of this network of ecology.”

Today, I’m taking a look at @Wanuskewin_Park’s newest exhibit, ‘Opimihaw.’

It was created by Indigenous artist, Mary Ann Barkhouse after she was inspired by the ecology of the Opimihaw valley, along with the reintroduction of the bison to the park. #yxe pic.twitter.com/tjglGKuKDn

— Brady Lang (@BradyLangSK) June 3, 2021

Barkhouse said all of the elements — no matter how big or how small — intersect in “this wonderful and very complicated way.” But at the same time, the history is consistently changing, and it’s an ongoing (movement) that gives the viewer the possibilities of renewal — both in physical and cultural aspects of the ecology.

That idea of consistent change aligns with Wanuskewin’s vision of showing Indigenous culture as a living culture — something that wouldn’t be seen in something like a museum where the past is the main focus.

Bison are also featured prominently in multiple pieces of the exhibit, something Kristoff added was crucial in the overall piece.

“When we had the bison return in the winter of 2019, it really did change the land for the better. They used to be here, this used to be their home. When they were all killed off, that changed the prairie landscape,” she explained.

When you enter the exhibit, you’re faced with two doorways into each room. Through one is a large space with a few pieces on the walls, a bison rocking chair faced against a carved wolf, and a table that Barkhouse created.

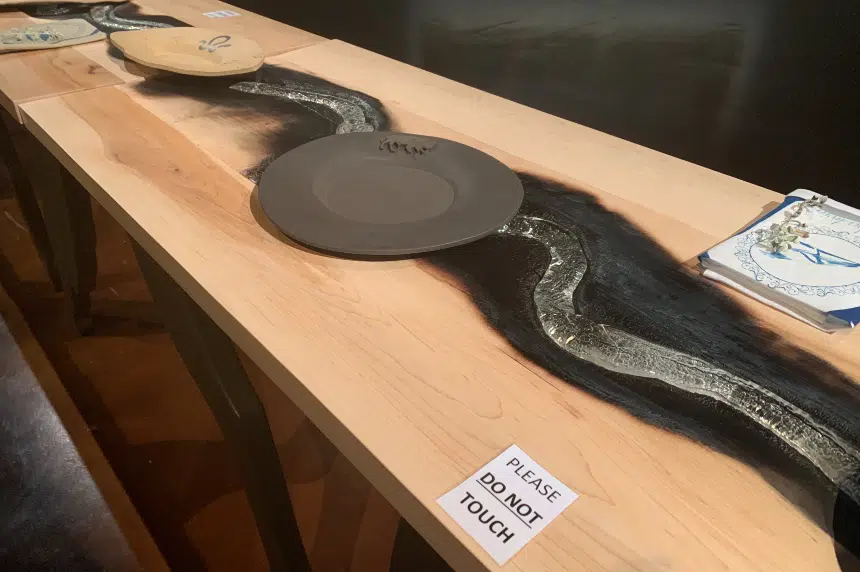

“This 18-foot-long table, I worked with glass artists that are here in Ontario … The table itself is of maple that was milled here in the Haliburton Islands. Then I drew the map of Opimihaw Creek onto the wood,” she explained. “They poured hot glass right into the outlines of the contours of the creek. I wanted to get that idea of every element interacting with each other.”

The table in Opimihaw has a map of the creek, filled with hot glass. (Brady Lang/650 CKOM)

She said the hot glass mixing with the maple gave the piece a truly Canadian feel. Ceramic dishes are throughout the table, all featuring different species from the land. Wood carved to resemble bison legs was also added underneath the large table.

“I’m trying to give the idea of the bison as the engineers of landscape,” Barkhouse explained.

The whole show was created through the pandemic lockdown in Ontario, Barkhouse added. The Vancouver-born artist also had a tie-in to the exhibition with residential schools.

Kristoff said Barkhouse’s mother was one of the youngest children to go to the Alert Bay residential school in B.C.

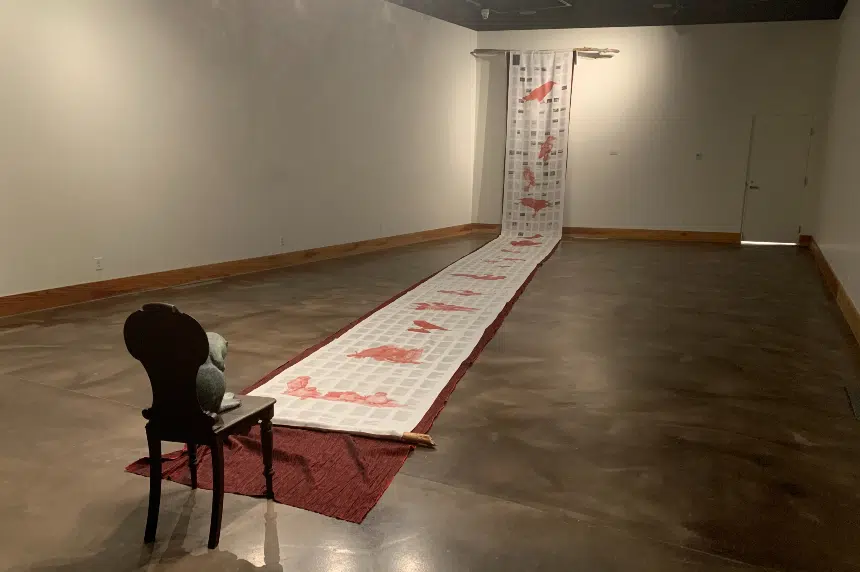

The piece is set in the other, smaller room of the exhibit. It’s a large tapestry, spread from the ceiling down the wall and onto the floor across the room.

What’s on the tapestry is extremely powerful.

Pictured is ‘Tapestry 1’ at Wanuskewin Heritage Park in Mary Ann Barkhouse’s Opimihaw exhibit. (Brady Lang/650 CKOM)

Made on linen, it is all 536 pages of the Truth and Reconciliation Executive Summary, printed with birds scattered across it — symbolic in Indigenous cultures of wisdom, authority, strength, and protection of the family.

“She grew up with this … Unless you’re in it, you don’t really realize that other people might not know the history as well as Indigenous people do,” Kristoff said. “With the Kamloops discovery, all of a sudden, there’s evidence … Hopefully this actually starts a path of healing and reconciliation.

“(The tapestry has) got a sculpture of a beaver sitting at a chair at the end, and the tapestry’s held up by beaver chews.”

That beaver is sometimes a nuisance, but in this case it’s a sign of resilience, explained the curator.

She explained what the piece felt for her.

“No matter what, we are strong, and we are beginning to heal,” Kristoff said.

Due to pandemic restrictions, Barkhouse hasn’t yet been able to take in her Opimihaw exhibit.

But with her work with Walker in the past, she’s excited to see it and how it all ties into the history at Wanuskewin.

“He gave me a lot of the background and the insight … a little window into what the vision was, and always has been for this place,” she said. “I look forward to the day when I can visit Wanuskewin again.”

The Opimihaw exhibit will continue at Wanuskewin until Oct. 29.