Sheri Zwack never heard the word “mom” from her daughter Olivia until the girl was 11.

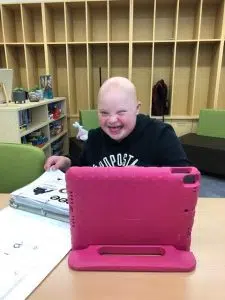

Now, thanks in large part to the help of a non-profit organization known as Ability in Me (AIM), 12-year-old Olivia can tell her mother “love you.”

“Olivia is literally like a beam of light in this world,” Zwack said. “She just emulates so much purity.”

Olivia is still in diapers and is non-verbal. She has Down syndrome and autism, an uncommon combination.

But Olivia has made progress working with an occupational therapist and speech pathologist at AIM, a non-profit organization that gives one-on-one support to kids with Down syndrome.

Unfortunately for the Zwacks, COVID-19 sent AIM’s programming online — and now the family from Warman is battling the Prairie Spirit School Division (PSSD) to get space for AIM programming at their local school.

Initially, Zwack said officials from the family’s school told her they’d be able to accommodate this request.

“We’re getting all excited. They even had the meeting with AIM,” Zwack said. “And then they said, ‘Nope.’”

COVID complications

In normal times, Olivia would attend AIM programming once a week on Tuesdays for an hour. When COVID forced the programming online, it was a difficult transition for the Zwacks.

While it was a disruption for many children to begin doing their schoolwork from home in early 2020, it was nearly impossible for Olivia.

“We tried the online option, (but it) did not go well with her at home,” Zwack said.

Zwack said Olivia’s autism can be the most significant disability she has, and it doesn’t allow her to learn easily online. To Olivia, school is school, home is comfort, and AIM is a “brown building” where she gets one-on-one time.

Sitting down to talk with a specialist through a screen at home isn’t something her brain allows for.

The Zwacks muddled through 2020 by requesting materials from AIM that they worked on with Olivia, but the arrangement wasn’t ideal. When Saskatchewan did away with all COVID restrictions this past July, the family thought their difficulties would be solved by the time the school year began.

Then AIM told families it would be continuing with online learning for a while longer.

Zwack then had the idea to ask the school division if Olivia could use some space at her school to do this online learning while her in-person therapy is unavailable. She thought it might work better than home, because Olivia associates school with learning.

“Why can’t we just try it and see if it works?” Zwack said, thinking the request was simple and reasonable.

Zwack’s request for Olivia was for 30 to 60 minutes of time for a virtual AIM therapy session once a week, where Olivia would be accompanied by her educational assistant or supervisor education resources teacher (SERT). These would only be needed as long as AIM was not providing in-person services.

The request wasn’t to overshadow strategies and recommendations provided by the school or interfere with normal instructional hours, Zwack said. They just wanted to give Olivia the opportunity to continue with the other ways she learns that work for her.

The school division said no. Zwack said the reason given by the school was that the arrangement didn’t fall within the guidelines of the division.

Sheri Zwack helps her daughter, Olivia, navigate her communication board while getting her a snack in their Warman kitchen. (Libby Giesbrecht/650 CKOM)All in the details

The decision didn’t make sense to Zwack. Aside from the request for a single support staff member to accompany Olivia during the weekly one-hour sessions, the arrangement would be of no cost to the division.

In an emailed statement, PSSD said it’s focusing on a “strong learning response for students following the interruptions caused by the pandemic” and is “implementing strategies to support increased mental health and wellbeing among staff and students during the course of this school year.”

The division acknowledged it has the responsibility to be the primary provider of school-based programs and services for all of its students and is required to provide a specific number of instructional minutes during each school day.

“Our professional learning support staff members provide specialized services for students who require additional supports,” the statement read. “It is recognized that parents may also choose to access assessments and/or therapy from private service providers.

“Private third-party services delivered directly to students during the school day are not possible in the school setting due to considerations including: ensuring student safety, liability, confidentiality, division programming, supervision and availability of space within school buildings.”

They said third-party service providers may access the school building after the school day, depending on the school’s booking and rental guidelines.

All in the details

Though the PSSD denied the Zwacks’ request, it did say Olivia could use space at the school — at a cost.

“They offered to bill us for use of the school and staff,” Zwack said.

When her husband spoke with PSSD director of education Darryl Bazylak, he was told the PSSD would not support the school day involvement of virtual AIM programming. Bazylak said specialist programming offered by the school division would be comparable to the services AIM provides Olivia with.

“Rather, we were given the option to utilize the Warman Community Middle School ‘space’ after the school day ended, as a means to facilitate the virtual AIM sessions with a support staff available to Olivia, with a billing of the respective staff member’s wage going to the AIM program and/or our family,” Zwack said.

“We did not accept this offered service.”

Zwack said the family did not care when Olivia received the space to do her AIM virtual programming and were entirely supportive of doing it outside of school hours. What is most important to Zwack is ensuring Olivia receives “elbow-to-elbow” time with specialists who can help her in her development.

“This kid is hard to program to begin with,” said Zwack, noting it usually takes a roundtable of occupational therapists, psychologists and speech pathologists to care for Olivia.

“Everyone has to be on cue with her needs.”

Zwack said she and her husband have been disappointed with the subsequent offers they’ve received for Olivia, especially in light of Bazylak’s assertion that PSSD therapies are comparable to those of AIM. An occupational therapist with the division said she was too busy to offer more than one session per month.

The need for extra support

Tammy Ives, AIM’s executive director since it opened in 2015, said its board is continuously reviewing the criteria to move forward safely with in-person programming again. It had hoped to be at that point in September, but with the rising COVID daily case numbers in the province at that time, the board felt the safest option for its high-risk clientele was to stay online.

The organization is currently working with an infection control consultant and assessing when it can begin a phased approach to reopening in-person appointments.

Zwack is incredibly grateful for the therapy AIM offers. The family pays a yearly fee for the services.

As part of AIM’s programming, Olivia has wiped windows to learn motor skills, gets one-to-one help with speaking and learns colours.

“When I think of how she struggled through this, it took a lot of work,” Zwack said. “You kind of hope that the school division and all these people that you trust … that they’ll be the same as they were in the health region, but it’s not.”

Ives said AIM programming is available to students in some school divisions, but it comes down to parents to arrange this service with their division, depending on their rules.

“Our program is parent-led, so basically it’s the parents who have been able to arrange with their school district or their school to have some of the programming happening virtually where the parents would join as well, but from a different location,” Ives explained.

Concerns for support go beyond Warman

Zwack’s frustrations now go beyond her initial request for support for Olivia.

“When appropriate external resources are needed for a child, the school division should respect those needs, and endorse and embrace the resources that can be accessed and utilized for a child,” she said.

Zwack said she sees these limitations constantly. The school division has touted its own occupational therapists and speech pathologists, but Zwack knows they’re overwhelmed with children needing assistance.

“They do so much for these kids, what they can do, but there’s just such a demand on them,” she said.

While the school division employs specialists like occupational therapists and speech pathologists, Zwack said most of the legwork she has seen has been done by SERTs.

“When school-based personnel are able to recognize their limitations and take steps to enhance them, it benefits the child, as well as everyone connected to that child,” Zwack said.

“Her educational assistants, staff at the school have been supportive,” she added, making it clear her frustrations lie with the school division, not with the staff who have worked with her daughter.

Further, Zwack takes issue with the lack of consistency among school divisions in the province, for which she holds the Ministry of Education accountable.

Brenda Erickson, the PSSD’s communication manager, said there are rentals in their schools for groups and activities held in the evenings or on weekends, “but not during the school day.”

Though she doesn’t know of any third-party programming that is allowed within the PSSD, Zwack has spoken with parents who have kids in other school divisions. She knows similar programming or arrangements like what she has requested for Olivia do take place at some Saskatoon schools, in addition to the school counsellors available.

A son of one of Zwack’s friends has been granted space for virtual mental health therapy, something she was told the school division had no problem doing.

“Where is the consistency here? Why is it that this area is a no (but) 10 minutes away it’s a yes? … It doesn’t make sense,” she said.

“I think the school division and the ministry have a long way to go when it comes to helping our kids with special needs. I don’t feel their supports are adequate enough.”

In Zwack’s opinion, 30 minutes with a speech pathologist and 30 minutes with an occupational therapist — a total of one hour — once a week would be “adequate” to help with Olivia’s needs.

The mom of two is finding it difficult to see their requests being denied by the school division as anything other than discriminatory.

Zwack and her husband have reached out to the Ministry of Education. Superintendent of sector support Rene Bilodeau told Zwack the ministry’s hands were tied because it does not have ties to the rules and regulations that are made within the school division.

Zwack said she was told by Bilodeau that the provincial government gives money to the school divisions, which are required to responsibly implement rules and regulations. All a school division is required to provide is 950 hours of school-based programming.

That accounts for the hours of time a child will spend in class between September and June. Lunch breaks are not considered part of the 950 hours.

“So why couldn’t it be then?” Zwack asked.

Kids left behind

Zwack worries kids like Olivia are falling through the cracks in the education system.

“They aren’t just something to write off in the system,” she said. “They do have qualities (and) they do have attributes that can contribute to society. There’s lots of kids and adults that work.”

That’s why she has taken her concerns to a number of people. Beyond Bazylak and Bilodeau, the Zwacks have also contacted NDP Leader Ryan Meili, PSSD trustee Adin Dereniwski and Warman/Martensville MLA Terry Jensen.

A change.org petition for Olivia to receive third-party support has received more than 500 signatures to date from professionals, teachers and other families across the country, many of whom have seen similar issues.

“I think they’ve epically failed kids with special needs across the board,” Zwack said.

Her request for Olivia is the same treatment she hopes all children with disabilities can receive across the province, especially with the extra challenges that have come as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I want to see change within the school divisions to have consistency across the board with third-party supports in the school divisions — all school divisions — for those with disabilities,” Zwack said. “They’re denying those rights. Period.”