Cindy Ghostkeeper-Whitehead knew something was wrong when she heard her friend’s voice on the phone on the morning of Sept. 4, 2022.

“She said bad things are happening. She said people are getting stabbed. She said, ‘My boy got stabbed,’ ” Ghostkeeper-Whitehead explained Tuesday at the coroner’s inquest into the stabbings that day, which left 11 people dead.

Ghostkeeper-Whitehead, a family wellness worker on the James Smith Cree Nation, said she got dressed and headed out immediately after that call. She said she still didn’t know the extent of what was happening, but she picked up her sister-in-law on the way into the village because she’d said she was home alone and scared.

“We came by the clinic and there was just police cars and the air ambulance and the ambulance,” said Ghostkeeper-Whitehead.

She said there were stabbing victims there, so she pulled in and talked to one family. That’s when she got another call asking her to check on Lydia Gloria Burns.

She got back in the car and went to Burns’ house.

“I remember pulling up to the yard and seeing something but, you know, I wouldn’t let it register, I think,” said Ghostkeeper-Whitehead.

“Another crisis response worker came to the truck and I got out, and I said, ‘Where’s Gloria?’ And she said to me, ‘She’s gone.’ And I said, ‘Well, where did she go? I have to go check on her,’ and she said, ‘No, Cindy, she’s gone. She passed.’ ”

The worker sat with Gloria for a while until Gloria’s brother Darryl arrived.

Then, Ghostkeeper-Whitehead said, one of Earl Burns Sr’s family members came and said he was hurt and no one was checking on him, so someone was sent to check on Burns Sr., only to find out that he’d died as well.

“It wasn’t until then that we realized – that I realized – what was happening, that we had lost all these members in our community,” she said.

Ghostkeeper-Whitehead said she and her husband went to the site of each attack to provide comfort and do what they could for the families. She said they stayed until the last body was taken away.

The response from the James Smith community itself has not been discussed so far during the inquest, which is frustrating to Mike Marion, the community’s health director.

“There’s no mention of our first responders that responded to these incidents as they were happening on the ground,” he said.

“There’s no mention of that – how we supported the community during this event – and it gets frustrating because we want the jury to know that we were part of this. We were part of this from the community with out support staff, our first responders (and) our first-aid people.”

When asked during the inquest, representatives from other agencies haven’t been able to say how the First Nation was supporting or helping its people during the attacks.

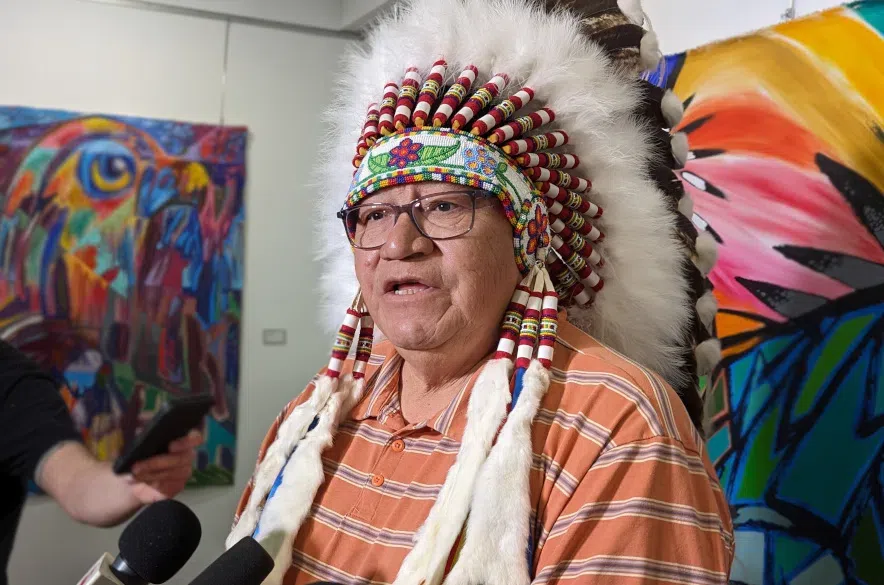

James Smith Chakastaypasin Band Chief Calvin Sanderson says he had a conversation about Myles Sanderson possibly coming to the First Nation on parole, but his parole was denied. (Lisa Schick/980 CJME)

Marion said he believes that if the jurors in the inquest are going to be making recommendations, then they need to know what resources have been and are available on the Cree Nation, and what they did and continue to do to help the band members and especially the families of victims.

He said it feels like the inquest feels like it’s being done “about them, without them.”

James Smith Chakastaypasin Band Chief Calvin Sanderson said the community is participating in the inquest and is looking for some specific recommendations.

He said one of the goals of the band’s leaders is for a national inquiry to be held, which would be more wide-ranging and could have more witnesses from the First Nation. The nation has pointed out in the past that there have been national inquiries for other, similar, incidents.

What is available

Ghostkeeper-Whitehead started working in the clinic on James Smith in 2017. She said they had a lot of programs in place for drug and alcohol awareness and education, anger management, grief support and inner child programs, and they’re still offered today.

There was also a crisis response team, which had significant training and took calls for incidents like suicide intervention and mental health first aid, and also answered calls related to domestic violence and grief support.

But after the attacks in 2022, she said they put a pause on some things.

“We took a step back. We were scared,” she said.

They’ve since worked hard to help the families of the victims, Ghostkeeper-Whitehead said, making sure they have what they need and organizing therapists for each family.

Ghostkeeper-Whitehead said the First Nation also has mental health therapists available for both adults and children.

Editor’s note: this story has been updated to clarify the chief’s interests in an inquiry