There’s a chance you could rush to your nearest emergency room only to find there are no doctors on site or worse, it’s closed.

That’s a scenario Saskatchewan NDP associate health critic Keith Jorgensen said could happen in at least three Saskatchewan communities.

Read more:

- Sask. NDP calls for an end to virtual health care in emergencies

- Culture review of Regina hospitals finds bullying, incivility, disengagement among doctors

- No timeline for Regina’s Urgent Care Centre to be open for 24 hours

Jorgensen said that based on information from Facebook or frontline healthcare workers he’s talked with, the issues faced by hospitals in Watrous, Kipling, and Davidson are “absolutely insane.”

He said the Watrous District Health Complex has experienced roughly 40 service disruptions so far this year and there’s no physical doctor on site.

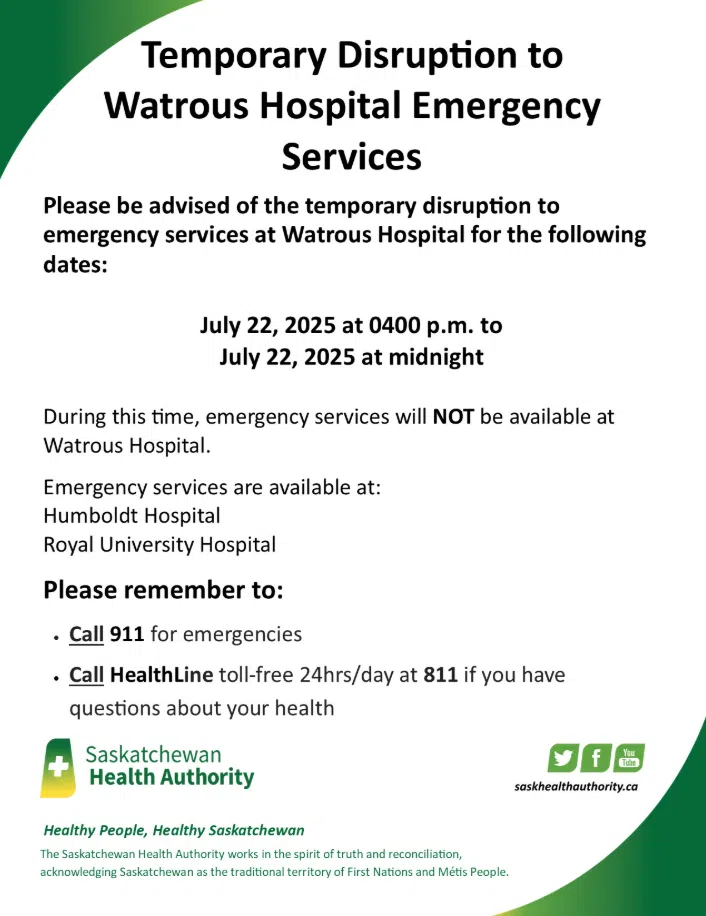

The Town of Watrous posted this notice about the temporary emergency services closure on their Facebook page at 9:13 a.m. on July 22. (Town of Watrous)

Similarly, Kipling Integrated Health Centre was closed this entire month, according to Jorgensen, and re-opened July 21 without a doctor physically present.

Davidson Health Centre closed in the late afternoon on July 22, and Jorgensen said the facility will rotate through virtual care for the rest of the week.

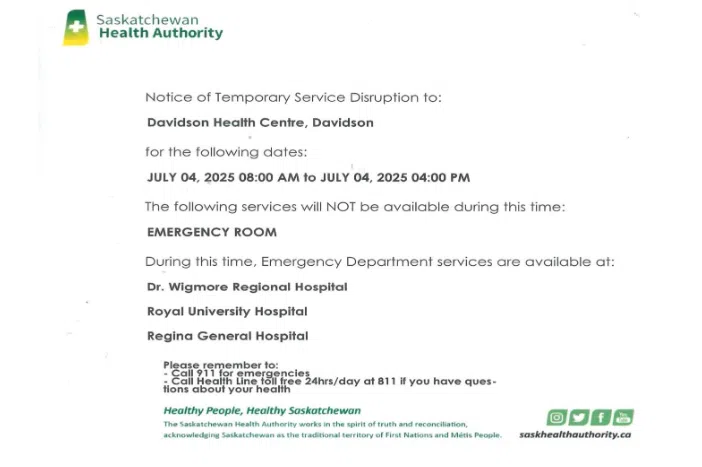

This notice was posted on the Town of Davidson’s Facebook page on July 4 at 9:31 a.m. (Town of Davidson)

They might not be the only hospitals in the province experiencing these issues, he said.

“I have no idea whether or not there’s three hospitals that are open with no doctors, or 30. We have no idea, because the government isn’t telling us, and it’s a tremendously dangerous situation,” Jorgensen said.

His criticisms of the government focused on three things: some hospitals aren’t open, others are opening without a doctor physically present, and neither of these situations are being effectively communicated with the public.

“The government is doing nothing to inform rural residents of this province of potentially dangerous situations that they face. It’s absolutely crazy,” Jorgensen said.

Searching for a solution

According to Jorgensen, the solution is simple: build a web page.

He said people should be able to search to see if a facility is open and whether a doctor’s on site.

Otherwise, he said, people are left in the dark on where they should go for treatment.

“There’s no way to actually know this without going to the facility and then realizing, ‘oh shoot, I drove half an hour in the wrong direction. This hospital has no doctor,’” Jorgensen said, calling out the government for its “gamble” on people’s lives.

That’s not the only technology-driven solution, though.

Jorgensen also spoke about making use of the cellphone emergency system, which just earlier this week notified people in Saskatchewan about a potential tornado nearby.

This system could broadcast hospital closures and service disruptions to people in the area and the bonus, according to Jorgensen, is that it wouldn’t cost much.

“To my knowledge, it costs nothing to send out these messages on a website or via cellphone,” he said.

Virtually no doctors

Not having doctors physically present doesn’t mean rural patients won’t have access whatsoever to a doctor, though.

The virtual doctor program, used by several rural communities, lets patients talk with a doctor through a web cam after being assessed by a nurse.

While Jorgensen has heard from dozens of rural residents who’ve spoken “glowingly” of virtual care, he said the option has its place in the health-care system.

According to Jorgensen, it should be used for routine medical issues, like refilling a prescription or treating a rash.

But, he said, it’s inappropriate to drive to an emergency room, “and then be told that you’re supposed to talk to somebody on the phone at the hospital. That’s insane in terms of how we notify people.”

While communicating through a webpage or cellphones are the first step, in the long-term, Jorgensen wants the provincial government to develop a plan for recruiting and retaining health-care workers in rural Saskatchewan.

The government did not respond to a request for comment by time of publication, but in April announced it was expanding its Rural and Remote Recruitment Incentive program, which offers up to $50,000 to new, full-time workers in nine high-priority occupations if they agree to work for three years in areas that are experiencing service disruptions, or are at risk of disruptions due to challenges around staffing.

The program now covers 70 communities in the province.

Also in April, the government announced a new digital advertising campaign aiming to attract American doctors to the province.

— with files by CJME News

Read more: