At first glance, it looks like mayhem.

Bodies spill onto the mat from every direction. A dodgeball sails where it probably shouldn’t. Shoes squeak, voices overlap and laughter cuts through the noise. There is no neat line, no whistle demanding attention, no obvious beginning or end.

Read more Saskatchewan Stories from Brittany Caffet:

- Jac Cashin defies Down syndrome limits at Saskatoon track meet

- ‘I’m a superstar’: Saskatoon preteen proudly represents Special Olympics

- Camp Easter Seal: The Saskatchewan summer camp that embraces disability

To an outsider, it might look like chaos — too loud, too loose and too unpredictable to be called a practice at all. But that’s before you take a closer look.

There are no whistles blaring, no hard-and-fast schedule to follow. These volunteer coaches take their time, giving every athlete the opportunity to thrive. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Kids approach the mat on their own terms. Some are eager, some cautious, some content just to watch. Coaches kneel to eye level, unhurried. They wait. They listen. They adjust. Nothing here is rushed and nothing is demanded. Each child is met where their abilities are, not where anyone thinks they should be.

This is the Down to Wrestle program, tucked inside the University of Saskatchewan Huskies’ wrestling room.

What’s happening here has very little to do with winning. It has everything to do with being seen.

The University of Saskatchewan is home to Canada’s first and only wrestling program for kids with Down syndrome. These athletes and volunteer coaches are redefining inclusion in the sport. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

For Clint Johnson, this room represents something that’s hard to find.

His five-year-old son, Mykola, has Down syndrome. He wants to play sports like other kids, but the opportunities are limited.

“The difficulty doesn’t lie so much in capability,” Johnson said. “It lies within the accommodation.”

There are many leagues, programs and teams available for athletic children in Saskatchewan, but very few of them are built with kids like Mykola in mind.

“There are a lot of sports out there, but they don’t necessarily accommodate Mykola’s ability,” Johnson said. “It’s tough for Mykola to be able to do the same things at the same level, but there aren’t enough kids with disabilities to make a whole club for it.”

Each Down to Wrestle practice ends with matches. The athletes cheer each other on, smiling as they go head to head. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Johnson said Down to Wrestle fills that gap.

“It provides a safe environment for for our kids to be able to compete, or to learn a skill that their typical siblings can do,” Johnson said, a smile spreading across his face as he watches Mykola barrel across the mats, laughing and full of energy.

Down to Wrestle started three years ago with a question: How do you create a wrestling program for kids with Down syndrome that doesn’t just include them, but actually serves them?

Anas Mohamad is one of the volunteer coaches leading the program, bringing lots of patience and determination to help the kids thrive. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

For Huskies head coach Daniel Olver, the answer came from experience. He’d seen what happens when kids with disabilities enter the traditional system without preparation.

“When they get to high school, they can join a high school team. They’ll just be thrown in with the rest,” Olver said. “When I was in high school, I wrestled with some kids with Down syndrome. That was pretty normal to us.”

Normal, but insufficient.

“The challenge is that they get lost in the mix,” he said.

Seven-year-old Eli once sat on the sidelines and watched cautiously. Three years later, he is an active participant in every activity the coaches throw his way. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Down to Wrestle, the first program of it’s kind in Canada, was designed to prevent kids from getting lost.

“What we want to do with these kids is built and develop them, so that when they get to high school the wrestling coaches recognize them already,” Olver explained. “They’re more than just a name on the sheet. They’re part of the program. There’s a spot for them within a team and within the city.”

That sense of belonging doesn’t happen accidentally. The program was built carefully, with input stretching far beyond the wrestling room.

Huskies head coach Daniel Olver said the goal of the program is to ensure that when these athletes enter the traditional sports scene, they won’t be lost in the shuffle. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

“We want to make sure that we’re doing a good job of developing them for success later in life and not just destroying what professionals are trying to teach them,” Olver said. “So this program was developed so that we can coincide with what the occupational therapists are teaching them.”

Intentional collaboration with pediatricians and therapists shaped every aspect of Down to Wrestle, from how practices are run to how rules are communicated.

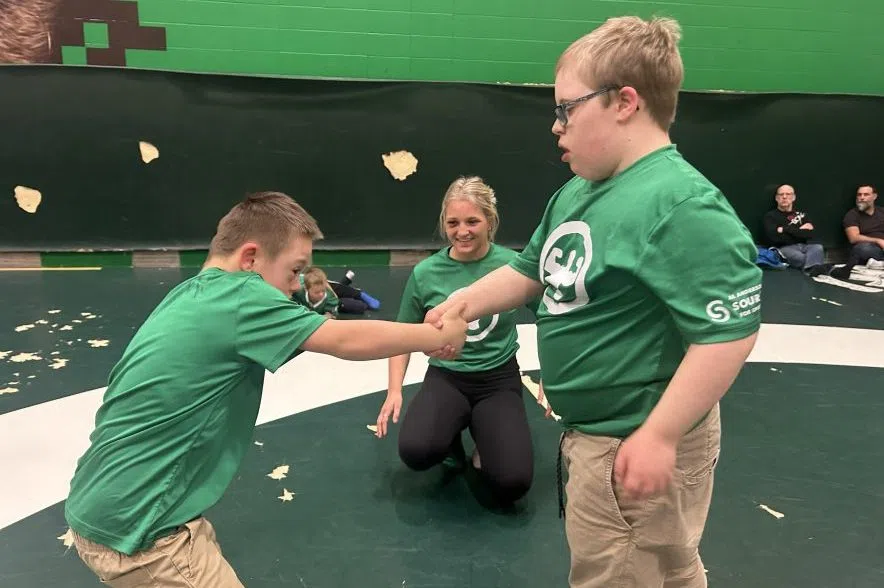

“Like the green shirt. Green means go,” Olver explained. “You wear the green shirt, you handshake and then you get to wrestle.”

Green shirt, shake hands, wrestle! The rules are laid out very plainly, helping athletes of all ages and abilities compete safely. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Clear signals means consent is also clear for the young wrestlers.

“And just being very clear with those rules so that when they go into their school, when they go into other places in the community, that we’re not disrupting their growth,” Olver said.

“When we developed our coaching handbook, we consulted with the professionals to make sure that we’re not doing any harm.”

Donovan Neudorf, the program’s lead technical co-ordinator, still remembers the uncertainty of the very first practice.

“We weren’t sure what this was going to look like,” he said. “Seeing the kids on the first day, they were very timid and they didn’t even want to play with the dodge balls.”

But that hesitation didn’t last long.

“Now you can’t get them to stop throwing the dodge ball at you!” Neudorf laughed. “And they’re really wanting to wrestle.”

The kids refer to Donovan Neudorf as their team captain. He’s been involved with the program since its inception three years ago. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Practices follow a rhythm designed for movement, learning and connection.

“Usually our first 10 minutes is just playing around, moving, warming up, getting some energy out,” Neudorf said. “And then we move into some sort of technique… and then we’ll end it with some wrestling.”

Along the way, the kids continually surprise the coaches.

“Last year, we did a challenge to see how long the kids could hang from the bar,” Neudorf recalled. “And we had little Eli hang there for like, over a minute! Just profound strength in his hands.”

For Taebyn Tulp, who developed the program’s curriculum, those moments affirm why the work matters.

“I think it’s great for any kid to learn grit and determination and discipline,” Tulp said. “We recognize that there’s a deficit for programming for these kids, and we wanted to create that space just for them.”

Taebyn Tulp has been wrestling for as long as she can remember. She said coaching Down to Wrestle is one of the most fulfilling things she has ever done. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

For Tulp, one unforgettable moment captured everything the program is about.

“At our Husky Duals this year, we had one of our athletes come and do a match at halftime,” she said. “Jac came out and did a match with Donovan… and I was sitting in the corner ugly crying.”

The moment on the mat lasted only a few minutes, but it carried the weight of years of effort, practice and trust.

“Seeing how excited Jac was to be out in front of all of those people and show off his talents as a wrestler, that’s why we do it,” Tulp said proudly.

The program hasn’t just impacted the kids. It’s changed the Huskies athletes, too — molding their patience, their perspectives and the way they see what’s possible for people with disabilities.

“First we shake hands, then we wrestle,” Coach Taebyn reminds the athletes as they get ready for another match. (Brittany Caffet/650 CKOM)

Tulp beams when she talks about what Down to Wrestle has become.

“This is probably the best program you’ll ever find in the country,” she said, eyes misty as she watched kids of all abilities moving, laughing and learning together on the mats. “It’s amazing, and I’m very proud of these kids.”

After practice, the gym falls quiet. The mats are stacked against the wall. The green shirts are folded and put away. Coaches linger for a moment, watching the last traces of energy drift from the room.

Every handshake, every laugh, every stumble and every small victory hang in the air as proof that in this space, every kid is seen and every kid belongs.

Ask 14-year-old Aidan Pike what it all means and he doesn’t hesitate.

“I love wrestling!”