By Glynn Brothen

An internal review on the RCMP’s response to the mass murder on James Smith Cree Nation (JSCN) and in Weldon is being released today, with a summary of 36 recommendations and effective practices Mounties used throughout the event and in its aftermath.

On Sept. 4, 2022, Myles Sanderson killed 11 and injured 18 others in one of Canada’s worst mass murder events. The search for Sanderson led to a three-day province-wide manhunt and culminated with a high speed chase near Rosthern on Sept. 7. Sanderson’s vehicle was stopped with a PIT maneuver and he died from an overdose shortly after his arrest.

These types of reports are conducted after mass casualty events to determine what lessons were learned, whether the RCMP provided an effective response and identify areas for recommended improvements. Similar reports have been created for the mass shooting incident in Moncton, New Brunswick in 2014 and a report is still in progress for the mass casualty incident in Portapique, Nova Scotia in 2020.

The areas recognized in the report included the initial response, the command structure, the major crimes unit response, air services, strategic communications, operational communications, mass casualty and victim response and pre-event intelligence.

The review team consisted of four brass from Alberta RCMP and included 24 investigative advisers from policing agencies across the country. Jason Stonechild, the executive director of justice of the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN) and retired deputy police chief of the Prince Albert Police Service was appointed as an independent observer and liaison to the JSCN community. He also provided cultural guidance to the review team.

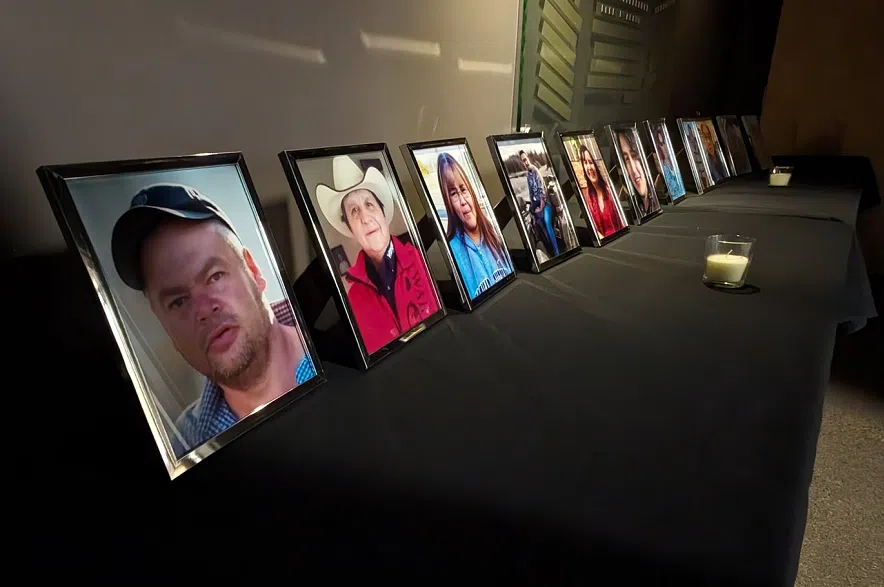

Pictures of the victims erected at the inquest into the mass murders on the James Smith Cree Nation and in Weldon. (Lisa Schick/980 CJME)

Reception issues

Poor radio reception was a concern brought up by virtually all members interviewed for the review. Members on scene were plagued by poor radio communication from the outset of the event, which was both a safety concern and hampered police efforts to locate victims and the suspect.

There were incidents on the James Smith Cree Nation where Mounties had to leave a residence or the victims they were attending to so they could stand outside for their radio to work effectively. Or, they had to rely on their cellphones. Later on, a piece of equipment was delivered to the area which enhanced radio coverage. The Saskatchewan RCMP relies on the provincial telecommunications network for radio communication and its known there are areas with poor reception, including on JSCN. For that reason, the review recommended the RCMP work with the province and band council to address radio communication issues. This was an issue that also came up in the Moncton case and its subsequent review.

Another technological issue officers faced is the mapping software in their vehicles was not working properly, which led to dispatchers not knowing where officers were stationed. It was recommended the mapping system be upgraded to share members’ movements.

This chilling photo was published in the RCMP report. Myles Sanderson evaded detection from responding officers by stealing multiple vehicles. This photo is from an RCMP vehicle’s dashcam showing how close Mounties were to a black Nissan Rogue that later became the identified suspect vehicle used by Sanderson. (submitted photo/RCMP)

Command Structure

With so many units, agencies and resources arriving on scene (549 police resources), issues with command structure led to some gaps in communication and location of resources. The report noted this issue didn’t lead to any issues with the outcome of the police response, but that there should be a ‘crimes in action protocol’ and command structure chart created for consistency and for the staff to know who is commanding them. It was also recommended technology be used to link all staff so all commanders are aware and up to date.

A key moment for this uncertainty was on Sept. 7 when the suspect vehicle was seen driving over 140 km/h the wrong way down the highway. During this time, an inspector and Chief Superintendent Teddy Munro were receiving information from a member monitoring the pursuit. The two supervisors decided to issue the directive to take the suspect vehicle off the road. Munro asked for his direction to “use whatever force necessary to stop the suspect vehicle” be transmitted over the radio. The member who issued the directive was confused because they believed it was the role of another officer to delegate.

There were other recommendations which suggested adding dedicated scribes to teams to handle the administrative tasks and take meeting minutes to ensure proper communication.

In this image taken from video, Canadian law enforcement personnel surround a residence on the James Smith Cree Nation on Sept. 6, 2022. THE CANADIAN PRESS/AP-Robert Bumsted

Air Services

The command structure also lacked a point person, known as an ‘air boss’ for the planes used to assist with this investigation. Because there was no flight coordinator or a single point of contact, it led to all commanders of different units contacting pilots directly. This confusion led to planes “essentially flying with little purpose” leading to the recommendation that in future major events an air boss must be identified early on. Because the planes were flying regularly, when the suspect was identified to be in Wakaw on Sept. 7, all three were on the ground refuelling, which delayed the search.

While it was not a recommendation, it was highlighted in the report that one of the Cesna aircrafts stationed in Saskatchewan was not operational during the event and the RCMP had to borrow a plane from Saskatoon Police. The federal government does not own the planes; they are leased by the Saskatchewan government.

“Although there is a recognized need to upgrade mission equipment and remedy the issues preventing the use of certain assets in order to resume those duties in support of frontline policing units, the provincial government seems reluctant to supply the funds,” the report said. “F Division air services have submitted multiple business cases to the province and now, following several high profile cases, are hopeful of making progress. All this puts Division Air Services in a difficult position as far as being able to efficiently assist with operations.”

Evidence

Due to the magnitude of this file, there were over 700 exhibits processed and over 40 separate crime scenes, including buildings and vehicles. Exhibit storage overwhelmed the nearby Melfort detachment and eventually had to be split between Prince Albert and exhibit storage in Saskatoon. Adding to the complexity, some of the crime scenes were far apart. Because so many officers were working on this file, it was recommended to explore the possibility of having civilian employees act as exhibit custodians to process evidence.

Dispatch

Civilian employees were also discussed in the report when it came to dispatchers and call takers employed by the RCMP. It was noted there are 15 staff vacancies in the Operational Communications Centre and only one of eight bilingual positions filled. Report writers pointed out that pay for the RCMP is significantly lower than in municipal services. During the incident, the centre received over 2,600 phone calls. Due to the workload (and radio communication issues) dispatchers abandoned doing safety check-ins with front line officers. Dispatchers from Regina Police Service were also brought in to assist with the high workload.

It was noted some calls were not forwarded to specific teams working on apprehending the suspect. For that reason, the report writers recommended that during major incidents, a major crimes investigator, a crime analyst and a dedicated dispatch supervisor work together to analyze calls in real time to determine trends or patterns.

Cultural Awareness & Victim Services

The number of victims in this case was numerous and family liaison officers were assigned to promote direct contact to victims and their families to help explain policing efforts, deliver next of kin notifications, and keep everyone informed. The report noted Indigenous Policing Services was crucial at fostering communication between investigators and the James Smith community.

Drawing from this event, it was noted members displayed cultural awareness for the needs from the community, specifically when it came to prayer circles and smudging as ceremonies for the deceased before their transport. It was also ensured that cleaning of various scenes also included coordinating cultural processes such as smudging the home or burning items covered in blood.

These takeaways led report writers to recommend the Saskatchewan RCMP create a ‘legacy document’ to be disseminated to outline various cultural considerations used to provide proper support for victim families.

A separate recommendation was written to address keeping family liaisons and media relations in contact for scheduled media announcements as Damian Sanderson’s family learned of his death from a media report.

People enter the public coroner’s inquest into the mass stabbings that happened on James Smith Cree Nation in 2022 in Melfort, Sask. on Wednesday, January 17, 2024. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Liam Richards

Myles Sanderson’s Criminal History and Parole Decision

Myles Sanderson’s criminal history was highlighted in the report and consisted of over 160 police interactions from 1996 to 2022. In his extensive criminal record, he had over 10 assault convictions and a lengthy history of violating court orders. At the time of the mass murder, Sanderson was wanted on a warrant for violating his parole release conditions.

Sanderson’s parole officer did not recommend for his release into the community as he was considered a high risk to reoffend. He breached his release conditions 19 days after his release from prison. He breached a second time and that’s what triggered his warrant. No cautions or flags were entered on Sanderson’s profile on the RCMP database.

The parole officer spoke with Melfort RCMP in July 2022 regarding Sanderson and his warrant and was assured by members that they would search for him. The report noted there was no RCMP record related to this contact found on any of the police computer systems.

The report made two recommendations for the RCMP to review the findings from the RCMP’s behaviour science unit on the psychological autopsy of Sanderson and review the findings from Correctional Service of Canada and the parole board on Sanderson’s release.