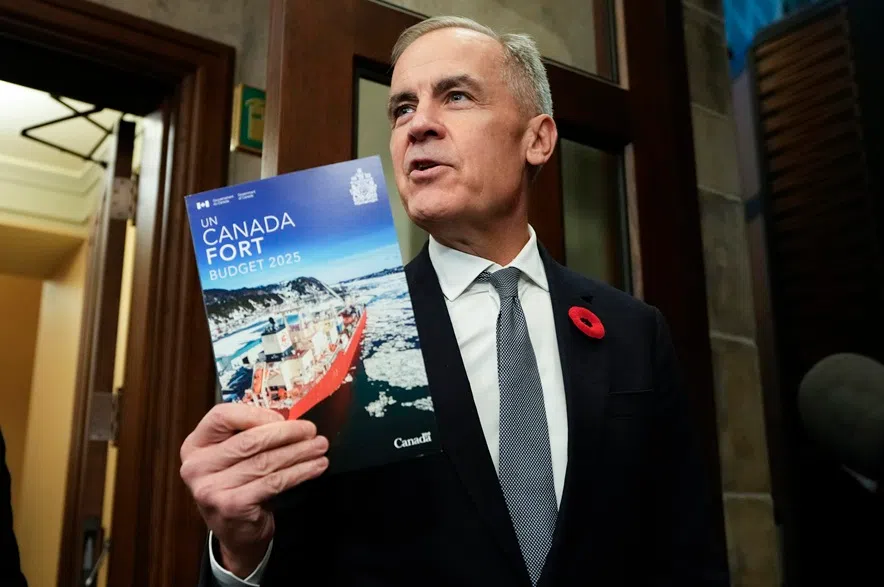

Mark Carney’s first federal budget is getting a C- grade from a Saskatchewan economics professor.

The budget, tabled in the House of Commons on Tuesday by Finance Minister François-Philippe Champagne, includes a deficit of $78.3 billion, nearly twice what was projected in Ottawa’s fall economic statement and nearly $10 billion higher than projections from the parliamentary budget officer in September. The budget also includes nearly $90 billion in new spending over the next five years.

Read more:

- Federal budget forecasts $78B deficit as Liberals shift spending to capital projects

- Budget 2025: Key numbers from the Liberals’ latest spending plan

- Canada’s economy shrank 0.3% in August, weak growth expected in Q3: StatCan

The Liberal government intends to continue running deficits in the coming years, but said the amounts will decrease to $56.6 billion by 2029-30.

Jason Childs, a professor of economics at the University of Regina, joined the Evan Bray Show on Wednesday morning to share his evaluation of the budget and how it will affect Canada’s economy in the year ahead.

While Childs said some of the spending characterized as “investments” in the Liberals’ budget makes sense, he said it won’t do much to address the affordability crisis in the short term, and the massive deficit could create some big problems down the road.

Listen to the full interview with Childs, or read the transcript below:

The following transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

EVAN BRAY: I was up relatively late last night trying to absorb the budget, reading documents, listening to interviews. I know you were doing the same. Maybe I’ll just start with your take on this federal budget.

JASON CHILDS: Well, let’s get the smart aleck out of the way here: I am so sick of buzzword bingo. I would really love governments of all stripes and at all levels to just present the numbers that said, “This is a big budget. There’s a lot of spending here. We’re looking at about 18, 19 per cent of every dollar that’s spent in Canada is going to be spent by the federal government in the under this budget, and we’re looking at a really big deficit.” So this is a big budget. There’s a lot of money flowing around in here and not a lot of really fine details.

If you think about how we spend our finances and manage our finances in our personal life, there’s this talk about good debt and bad debt. Does that apply to the federal government? I feel like that’s the narrative that they’re pushing, that “This isn’t debt, this is an investment in our future.” Do you see it that way?

CHILDS: To a degree, yes. The idea is pretty sound if we’re actually buying assets that are going to generate meaningful economic activity in the future, then thinking about it a little bit differently than just spending – one and done, it’s gone – makes a lot of sense. The problem, and this is always the case, comes in the implementation. It’s really easy and tempting for governments to stuff spending that isn’t meaningful investment in the future into that budget and say, “Look, these are investments” when they’re never going to return anything to us. And we’ve seen some of that in this budget. If you go through the list of projects that are in there on page 103 of the budget. For those who are taking notes at home, you’ll see some of those investments aren’t really investments.

Give me an example, Jason.

CHILDS: Community centers, things like that. They’re nice to have, they’re not a bad idea, but they’re not investments. They’re consumption spending.

I feel like I’m in actually one of your classes, because we’re talking assets and liabilities and good debt and bad debt. Is that part of the strategy of Prime Minister Mark Carney? He’s really making this distinction between the operational budget and the capital budget. Why is that?

CHILDS: Some of it’s salesmanship. Some of it’s going to be a little bit of a magic trick. “Pay attention to my left hand when my right hand picks your pocket.” Some of it is honest truth in reporting and financial numbers. Again, it’s that distinction, the difference between types of spending and what what we can expect it to do, and whether that spending is a good idea. Now we’re not in a great fiscal position here. We’re better than some, we’re worse than others, and when you roll up the whole thing, you’ve got this problem of provincial debt, municipal debt, federal debt, all adding up to a lot more than what we’re talking about. So even though we’re in a little bit of a tough position here, if there’s an investment opportunity that is a real investment opportunity, it might make sense to go after that.

The growing debt is something that has obviously a lot of eyes on it, lots of speculation. We know it’s $78.3 billion. In fact, it’s going to be $300 billion in the next five years. That seems like a big deal, the amount of money, for example, that we pay to service the debt alone. At what point does the debt become problematic, or is it already?

CHILDS: I’m of the opinion it’s already problematic. And remember, a budget is an aspirational document. This is if everything goes as exactly as we imagine it’s going to go, then we’re going to be $78.3 billion in debt. If we don’t get the GDP growth we’re expecting, or if we get some other need for expenditure, we’re going to blow past that. And if you look at particularly the projections further out for the year after and the year after that, which you talked about with that $300 billion total spending, we’ve never hit that. This government has never hit those marks. So next year, there will be something else come along and the forecasted deficit will be meaningless. The actual deficit that we’ll see in the next budget will probably be larger, and at some point we’ll need about a 15 per cent GST by the end of what they’re forecasting here to service the just the federal debt. That ignores provincial and municipal debt, which is also going to have to be serviced, and all that servicing comes out of one set of pockets, and that’s the taxpayers of Canada.

I hate the word servicing, because it essentially implies to me that we’re basically paying the interest we need to. We’re keeping our nose above water. But we want to dig down. We want to get rid of that debt. We’ve seen federal governments, obviously, play a role in incentivizing economic growth. How do you see the approach that has been taken here by the Mark Carney government to do just that? Have they dug too deep, or have they struck a balance that is probably where we need to be, given the environment we’re in right now?

CHILDS: It’s going to come down to the details. In a lot of cases, I don’t think this hits the mark. I think what they needed to be doing was changing some of the legislation and some of the red tape here, rather than creating workarounds and throwing more money, through tax credits, at the problem. For example, there’s big changes to the rates at which projects or capital investments can be written down. That’ll help, but if I’m worried about losing title to the property that I buy to build a factory on, it doesn’t matter how quickly you let me write it down against taxes. If you know it takes six years to get a environmental approval, it doesn’t matter how quickly I can write down the capital expenditure once I start building. We’ve got all these other things in the way, and I haven’t seen any movement on those other than this centralization of power in the PMO (Prime Minister’s Office) that allows you to bypass existing legislation, existing law.

Six months from now, am I going to notice a difference in my bank account? Am I going to notice a difference at the grocery store? I don’t feel like that’s the case. Do you agree, Jason?

CHILDS: I agree with you 100 per cent. Just for fun, one of the things I do with these budget documents is I just do a general search to find out how many times things like “Saskatchewan” appear. Total of nine times over nearly 500 pages. And that’s it. This budget is not targeted at Saskatchewan at all. The only thing that really comes up in any meaningful way is the AgriStability program. And people have commented on that, that it’s just not going to do what we need it to do there.

There is some sector relief and some changes to employment insurance for those that are affected by tariffs. But I’ve said this before, and I’m curious to hear your opinion. I feel like that helps auto workers but does nothing for farmers. Farmers aren’t going and getting retrained to work in a different industry, as a rule.

CHILDS: No. And if you’re if you’re working a farm out of Assiniboia, or some more remote area of Saskatchewan, your local opportunities are really limited. It’s not like you’re in Toronto when you can go, “OK, I’m going to switch from assembling cars to assembling dishwashers or something like that.” None of these things help us. And what I find really aggravating is the problem with canola and China is designed to protect those auto workers, and there’s been no relief for us, in a meaningful way, on that front.

If you’re a person that that accepts these as investments in our future, it’s short-term pain for long-term gain. Do we have a sense of the timeline on what we’re hearing from government versus the reality of when we’ll start to see things move from being in the negative to being in the positive?

CHILDS: Not in the time span of this budget. We’re looking five years out. I don’t they’re forecasting a return to about two per cent real GDP growth in about ‘27 or ‘28, but I think that’s wildly optimistic. I don’t see these these projects – once they even get started, once we get shovels on the ground – I don’t see them paying dividends in terms of anything other than the benefit of construction in the next five to 10 years.

I’ve got a text here from Linda saying, “I keep hearing about debt-to-GDP ratio, although I don’t completely understand.” Can you give us just the Reader’s Digest version of why this measure is something that’s important to follow?

CHILDS: It tells you how much we owe, relative to what our potential income is. So based on this, in ‘26, ‘27 – these are numbers right out of the budget – this is the projection we will owe 43.1 per cent of everything that gets produced in Canada. That will be our debt. So if we didn’t consume anything for nearly six months, we could pay off all our debt. That’s just at the federal level. When you roll up all the provincial debt, that number’s over 100 per cent, so we’d have to eat nothing for a year to pay off all our debt.

Would you give the budget a grade?

CHILDS: This is a document I would love to have had a week to have gone through. I’m thinking C-. It’s a bit of a Hail Mary. We’re talking about $40 billion or so in infrastructure spending. Well, that doesn’t buy that much infrastructure and we aren’t seeing a real wind down or change in any of the underlying conditions, or not many of them, and that’s what worries me more than the specific numbers.

–with files from The Canadian Press